On Twitter, I’ve been charting 101 British string quartets composed between 1918 and 2018 – not really a “best of” list (which is impossible), but more to showcase the incredible diversity of composers still willing to add to the imposing existing repertoire of works, using a wide range of styles and techniques. I’m also not saying that British quartets are better than those from other geographies – it’s simply that I’ve studied the music of Britain in more depth, and have a little more chance of identifying the landmark works. So here is the (slightly revised and expanded) list in full, complete with comments and also direct links to recordings where available – surprisingly, the vast majority of them have been recorded. To see the original posts, go to Twitter and search for #BSQ and “string quartet”.

1. Edward Elgar: String Quartet in E minor, op 83 (1918).

One of the three chamber pieces of this period that were to be Elgar’s last major works. It was premiered at the Wigmore Hall on 21 May, 1919. https://bit.ly/2DGQkFm

2. Charles Villiers Stanford: String Quartet No 8 (1919).

His final quartet, still in line with German chamber music tradition, in a minor key and generally introspective. It remained unpublished and unperformed until 1968. https://bit.ly/2WhnOkY

3. York Bowen: String Quartet No 3 in G major, op 46(b) (1919)

Only two of Bowen’s very English-sounding quartets have survived, the first is lost. The third is the more lyrical, melancholic and elusive of the two survivors. https://bit.ly/2J98LpD

4. E J Moeran: String Quartet No 1 in A minor (1921).

Well received, then quickly forgotten. Energetic, melodic allegro; autumnal and quiet andante con moto; restless rondo, in turns nervous and reflective. https://bit.ly/2GPvSmz

5. William Walton: String Quartet No 1 (1922).

Walton himself was dismissive of this early quartet – “full of undigested Bartók and Schoenberg” – but there’s no denying the power of the final fugue. https://bit.ly/2DNYrQC

6. Bernard van Dieren: String Quartet No 4 (1923).

Scored for an unorthodox combination of two violins, viola and double bass. The unusually accessible (for van Dieren) final dance movement at 16.45 is the easiest starting point. https://bit.ly/2UWvFmi

7. Rutland Boughton: String Quartet in A major (1923).

Boughton wrote two quartets in 1923. This one is subtitled On Greek Folk Songs, but folk sources are not specified. Uses classical form with rhapsodic passages. https://bit.ly/2JcHzqi

8. Arnold Bax: String Quartet No 2 in A minor (1924-5). Composed at the same time as the 2nd Symphony. “Complex, brooding, as harmonically daring as Bax ever ventured”. https://bit.ly/2VI5vIG

9. Rebecca Clarke: Two Movements for String Quartet (1924-6).

Comodo Amabile is a single movement from an intended full quartet, composed in 1924. It was followed two years later by Poem (aka Adagio). OUP published the two together in 2004. https://bit.ly/300F4xc

10. Frank Bridge: String Quartet No 3 (1926-7).

Bridge’s Third Quartet “contains the best of me I do not doubt”. Anthony Payne called it “The first work to show Bridge’s late manner in full flight, all impurities filtered out”. https://bit.ly/2UYTKt3

11. Imogen Holst: Phantasy Quartet (1928).

This student work, modal and pastoral in style, won the Cobbett Prize for an original chamber composition, and was first broadcast in 1929. Revived at the BBC Proms in 2013. https://bit.ly/2LlzYbl

12. Charles Wood: String Quartet in F major.

Written during the war but only published (posthumously) in 1929, the quartet opens with a sombre, fugal poco adagio. Wood, an influential teacher, composed six quartets. https://bit.ly/2IYZW2n

13. Gordon Jacob: String Quartet No 2.

It was first played at Conway Hall on 5 November 1931. “[Hubert] Foss and [Ralph] Greaves both tell me that the 2nd Quartet was the best thing in the programme” wrote Vaughan Williams. https://bit.ly/2vyX4AL

14. Bernard van Dieren: String Quartet No 5 (1931).

The exact date may be earlier: Denis ApIvor (who called out the “beautiful Adagio” of No 5), says Peter Warlock saw the score before his death in Dec 1930. https://bit.ly/2GU7Dnc

15. John Foulds: String Quartet No 9. Quartetto Intimo (1932).

Championed for years by Malcolm Macdonald, whose work led to its first performance in 1980 by the Endellion Quartet, followed by this landmark recording. https://bit.ly/2PNADkz

16. Granville Bantock: In a Chinese Mirror, (1933).

Genial and melodic work derived from his first set of Songs From the Chinese Poems (1918). In need of revival (last broadcast by the Lyric Quartet on 13 Oct 1996). Score and parts available. https://bit.ly/2Wp8qmr

17. Edric Cundell: String Quartet in C, op 27. (1933).

This “unflaggingly energetic” quartet won first prize in the Daily Telegraph chamber music competition. Cundell was Principal at the Guildhall School of Music from the late 1930s until the late 1950s. https://bit.ly/2H1CFL1

18. Lennox Berkeley: String Quartet No 1, op 6 (1935).

More astringent than might be expected, but still classically poised in the familiar Berkeley manner and full of masterly counterpoint. https://bit.ly/2LnYMQc

19. John Blackwood McEwen: Quartet No 15 (1936)

Subtitled A Little Quartet in modo scotico . Not really little. McEwan wrote an impressive cycle of 19 quartets (17 numbered) between 1893 and 1947. https://bit.ly/2vAHsg9

20. Arnold Bax: String Quartet No 3 (1936).

Written for the legendary Griller Quartet. Third movement contest between “malicious” scherzo and “dreamy, romantic” trio (the scherzo wins). https://bit.ly/2WpK7F0

21. Elizabeth Maconchy: String Quartet No 3 (1938).

Although brief (in a single movement) it was the first of her 13 quartets to really reveal her individual voice. It was played at the Proms in 2013. https://bit.ly/2vFwYvM

22. Priaulx Rainier: String Quartet in C minor.

Nothing from a British-based composer like this had been heard before, it points towards the mature quartets of Britten and Tippett. She awaits revival. https://bit.ly/2ZWW9bh

23. Arthur Bliss: String Quartet No 1 in Bb (1940).

Like Britten’s first quartet (1941), this piece was written in America and first performed there. Bliss returned to the UK in 1941, leaving his family in California. https://bit.ly/2VOpYLK

24. Lennox Berkeley: String Quartet No 2, op 15 (1941).

The slow movement in particular is classic, French-influence, lyrical and free-form Berkeley at his most beautiful, but surrounded by structured, energetic and idiomatic outer movements still surprising in their ferocity. https://bit.ly/2WurwIc

25. Michael Tippett: String Quartet No 2 in F# major (1942).

A brilliant quartet full of lyricism and dancing rhythms, with (from 6.31) an unsettling 2nd movement Fugue echoing Beethoven’s C# minor, op 131. https://bit.ly/2LoaHNS

26. Egon Wellesz: String Quartet No 5, op 60 (1943).

Wellesz fled to England from Austria in 1938. The fifth quartet marked his return to composition after all the trauma had silenced him for several years. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHBmYIVfeRE

27. Vaughan Williams: String Quartet No 2 in A minor (1942-4).

First performed by the Menges Quartet on 12 October 1944 (the composer’s 72nd birthday) at one of the wartime Myra Hess National Gallery lunchtime concerts. https://bit.ly/2DSbOz1

28. Benjamin Britten: String Quartet No 2 in C major, op 36 (1945).

“A most original and beautiful composition, one of the compositions of the century” (Michael Kennedy). Final movement Chacony shows the influence of Purcell. https://bit.ly/2ZXFEvA

29. Imogen Holst: String Quartet No 1 (1946)

Imogen Holst found her personal voice in the 1940s in works such as this and the Serenade for flute, viola and bassoon, including a move away from modal harmony towards scales of her own devising, increasingly dissonant. https://bit.ly/2VFc12Q

30. William Walton: String Quartet No. 2 in A minor (1947).

Closely related to his Symphony No 1. I first heard it in the vintage 1949 recording by the Hollywood String Quartet. https://bit.ly/2ZXN2qD

31. William Wordsworth: String Quartet No 3 (1948).

“One of the composer’s most powerful works” (Paul Conway). “Of dark and sombre beauty” (Michael Kennedy). First performed 1 July, 1948 at Cheltenham. https://bit.ly/2VEJRVJ

32. Peter Racine Fricker: String Quartet No 1, op 8.

A single movement work, influenced by Michael Tippett’s first three quartets, by his teacher Mátyás Seiber, and by Seiber’s enthusiasm for Bartok. https://bit.ly/2WlF7kM

33. John Joubert: String Quartet No 1 in A Flat Major.

The composer’s opus one, and the first of his three quartets, clearly influenced by William Walton but full of its own vitality. https://bit.ly/2ZO1KAu

34. Matyas Seiber: String Quartet No 3, Quartetto Lirico (1951).

Dedicated to the Amadeus String Quartet and recorded by them. The calm of the final Lento is very characteristic of Seiber’s later works. This was his last quartet. https://bit.ly/2VeJaD1

35. Elisabeth Lutyens: String Quartet No 6, Op.25 (1952)

In two movements. Shows her mature style, written over a single 12 hour sitting and dedicated to Francis Bacon – who could also work at great speed. https://bit.ly/2hWszBg

36. Robert Simpson: String Quartet No 2 (1953).

A single movement piece, perhaps the central movement of a trilogy (numbers 1, 2 and 3), bridging the cheerfulness of the first with the melancholy of the third. https://bit.ly/2LhTtBE

37. Carlo Martelli: String Quartet No 2 (1954).

As a young composer, until the early 1960s, Martelli enjoyed more success than any of his generation (Maxwell Davies, Birtwistle, Richard Rodney Bennett). A BBC broadcast of this quartet is available. https://bit.ly/2IZh1JM

38. Alan Rawsthorne: String Quartet No 2 (1954).

Rawsthorne’s own favourite and (said John McCabe) “one of the finest from any British composer”. The finale (theme and three variations) is particularly striking. https://bit.ly/2PKMMXh

39. Roberto Gerhard: String Quartet No 1 (1956).

Showing off his personal combination of classical tonal form and serialism that became important in his later works. https://bit.ly/2GUCRL2

40. Brian Boydell: String Quartet No 2, op 44 (1957).

With his second quarter, the Irish composer moved beyond “celtic twilight” to forge his own language, including use of the octatonic scale. https://bit.ly/2JiYlnk

41. Wilfred Josephs: String Quartet No 2, op 17 (1957-8).

Josephs wrote four quartets between 1954 and 1981, along with much other chamber music. All his music is neglected these days, but especially the chamber music. https://bit.ly/2Y73Ium

42. Arthur Benjamin: String Quartet No 2 (1959).

Australian-born Arthur Benjamin was a diverse and prolific composer who deserves to be remembered for more than just the Jamaican Rumba of 1938. His first quartet (Pastoral Fantasy) dates back to 1923. https://bit.ly/2PRQIFG

43. Peter Maxwell Davies: String Quartet No 1 (1961).

Very early Max – Plainsong fragments, influences of Monteverdi, Bach, late Beethoven and Schoenberg, overshadowed these days by the Little Quartet series and the 10 Naxos Quartets. https://bit.ly/2IXDMh2

44. Hugh Wood: String Quartet No 1 (1962).

The first of five. “A vivid essay in Schoenbergian tension, scampering expansions and sinister urgency.” (Rob Barnett). https://bit.ly/2LlgUKu

45. Bernard Stevens: String Quartet No 2 (1962)

His chamber music masterpiece, full of fluid counterpoint and balancing his interests as a tonal composer with an exploration of serial techniques. His use of two 12-note rows divided into major and minor triads for contrast is an audible process. https://bit.ly/2XXRPXe

46. Edmund Rubbra: String Quartet No 3 (1963).

In three, interlinked movements. “Lyrical song is the motivating force of the work” said the composer. https://bit.ly/2vBIGYA

47. Benjamin Frankel: String Quartet No 5 (1965).

His greatest quartet and one of his finest works. In 1967 Stanley Sadie wrote: “a gentle, attractive piece, tonal (although 12 note) full of smooth sweet intervals [and] swaying, reiterated figures”. https://bit.ly/2vxNk9U

48. David Wynne: String Quartet No 3 (1966).

Michael Tippett was a supporter of this Welsh composer of five quartets, and Bartok a significant influence. This piece is tough and uncompromising. https://bit.ly/2DLZmRw

49. Graham Whettam: String Quartet No 1 (1960-67)

The first of four quartets. The string chamber music is as central to Whettam’s output as the symphonies and solo percussion works are. https://bit.ly/2Vh4oQD

50. Cyril Scott: String Quartet No 4 (1968).

Incredible that Scott (flourished circa 1900s) was still composing in the late 1960s when he was in his late 80s and his harmonic language was still evolving. Amazing also to have a recording. https://bit.ly/2IY7Qcj

51. Hans Gal: String Quartet No 3 in B minor, op 94 (1969). Hans Gal’s first two quartets were written before his exile to the UK. The last two are Edinburgh works. This one premiered by the Edinburgh Quartet in 1970. https://bit.ly/2DMsYho

(51A. I couldn’t miss out the String Quartet No 5 from fellow émigré composer Joseph Horovitz, first performed in 1969 at the V&A Museum. “His most profound work”: Daniel Snowman.)

https://bit.ly/3bZ2adr

52. Lennox Berkeley: String Quartet No 3, op 76 (1970).

Composed three decades after its predecessor, and just after his Third Symphony. “A beautiful product of Berkeley’s full maturity” (Hubert Culot). https://bit.ly/2LmZq0k

53. Elizabeth Maconchy: String Quartet No 10

Premiered in Cheltenham, July 1972. In one movement. Everything derived from (and subsequently linked by) the opening viola solo. https://bit.ly/2Jd7vC1

54. Robert Simpson: String Quartet No 4 (1973)

Appeared two decades on from No 3, it was the first of three to come out in rapid succession, written as extended variations on the three Beethoven Rasumovsky Quartets. https://bit.ly/2UUKl5D

55. Malcolm Arnold: String Quartet No 2 (1975).

“Disturbing, beautifully crafted, on a par with the greatest contemporary quartets of Britten, Simpson or Shostakovich” (Piers Burton-Page). https://bit.ly/2UYrgzp

56. William Alwyn: String Quartet No 2 Spring Waters (1975).

“My careless years, my precious days, like the waters of springtime, have melted away” (Turgenev). Alwyn was 70 years old. https://amzn.to/2DNs5FH

57. Benjamin Britten: String Quartet No 3, op 94 (1975).

Britten’s last completed major work and perhaps his most personal, especially the E Major passacaglia finale. https://bit.ly/2GXuvSB

58. Alexander Goehr: String Quartet No 3, op 37 (1976).

“Involvingly knotty – a composer as released as much as trapped by tradition” (Tom Service). It’s “assured serial modality” (Grove) was surprising following on from his modal white note setting of Psalm iv. https://bit.ly/2H1013E

59. Edmund Rubbra: String Quartet No 4, op 150 (1977).

Rubbra’s final quartet, in two concentrated movements with themes relating to his 11th Symphony. Dedicated to Robert Simpson, but also a memorial piece for a friend, ending peacefully. https://bit.ly/2vBgDbG

60. Minna Keal: String Quartet, op 1 (1978).

Pressured in 1929 to give up composing, Minna Keaal was encouraged to resume after her retirement (aged 69) by Justin Connolly, this concentrated quartet was her first official new work. https://bit.ly/2VFWBv4

61. Thomas Wilson: String Quartet No 4 (1978).

Commissioned by the Edinburgh String Quartet, it’s a single movement piece but with five distinct sections. Uncompromising, abstract. “Its ideas and cells are unfolded with economy and elegance.” https://bit.ly/2Y4narr

62. Andrzej Panufnik: String Quartet No 2 Messages (1980).

Abstract, yet highly personal work drawing on memories from the composer’s Polish childhood of sounds produced by telegraph wires vibrating in the wind. https://bit.ly/2UX9Jrg

63. Brian Ferneyhough: String Quartet No 2 (1980).

Ferneyhough’s six string quartets embody the definition (by Christopher Fox) of “The New Cmoplexity”. “Multi-layered interplay of evolutionary processes occurring simultaneously within every dimension”. https://bit.ly/2j5vqYe

No 64. David Matthews: String Quartet No 4, op 27 (1981).

Matthews has written 13 quartets. He calls this one the closest he’s got “to the classical archetype”. The emotional centre is the third movement adagio sostenuto. https://bit.ly/2DIOMup

65. William Alwyn: String Quartet No 3 (1984).

His last major work. In two movements, the long and mostly elegiac second movement adagio includes a characteristic waltz at its centre. https://bit.ly/2GZ8xzZ

66. Elizabeth Maconchy: String Quartet No 13 Quartetto Corto (1984).

Only eight minutes long and highly compressed, with three identifiable movements within, including an expressive central slow movement. https://bit.ly/2IXwwSb

67. Julian Anderson: String Quartet No 1 Light Music (1985).

Perhaps the first example of “spatial music” from a British composer, but not performed until 2013 at the Aldeburgh Festival (by the Arditti String Quartet). https://bit.ly/2PMRHqY

68: William Mathias: String Quartet No 3, op 97 (1986).

His last quartet (though another was in progress at his death). Shostakovich is an influence on the dark first movement, Britten in the dance-like finale. https://bit.ly/2vywQ1e

69. Alan Ridout: String Quartet No 3 (1987).

Ridout’s quartets are tightly constructed, very individual and can be quirky and rugged, but also surprisingly lyrical. No 3 begins with an intriguing fugue. https://bit.ly/2VINWrK

70. James MacMillan: String Quartet No 1 Visions of a November Spring (1988, rev. 1991).

‘Sheer frenzy, craziness’ (MacMillan). Janus-like synthesis of contrasting old and new influences. First movement built around a sustained, single note. https://bit.ly/2LfDhko

71. John Tavener: String Quartet No 1 The Hidden Treasure (1989).

“I dreamed The Hidden Treasure in the form of twenty-five notes. […] as a Byzantine palindrome representing ‘Paradise'”. (John Tavener). The steps of the Passion and Resurrection of Christ are suggested throughout.

https://bit.ly/2vyWWBi

72. Berthold Goldschmidt: String Quartet No 3 (1988-9).

Reflects the 85 year-old composer’s renewed memory of anti-semitism, set off by a visit to Germany. (The 2nd Quartet of 1936 had first marked his “fearful joy” at escaping the Nazis). https://bit.ly/2GXlIBz

73. Robert Simpson: String Quartet No 14 (1991).

First since No 6 (of 1975) to adopt a four-movement classical design. “One of the most beautifully transparent quartet slow movements this century. (Matthew Taylor). https://bit.ly/2Wkfv7Q

74. Michael Tippett: String Quartet No 5 (1990-91).

Paired down textures and a renewed lyricism recalling his much earlier work. Soaring solo violin in the 2nd movement inspired by song of the nightingale. https://bit.ly/2PFzifC

75. Graham Fitkin: Servant for String Quartet (1992).

Starts with characteristic rhythmic unison, then opens out into two, three and four part polyphony. Fitkin has composed six quartets to date. https://bit.ly/2ZNQ40H

76. Daniel Jones: String Quartet No 8 (1993).

His very last composition. Giles Easterbrook and Malcolm Binney created a performing edition that was used for the Chandos recording. https://bit.ly/2PECzvL

77. Nicholas Maw: String Quartet No 3 (1994).

Set as a five movement in one structure that culminates (like Britten’s Third) with a concluding, expressive passacaglia. https://bit.ly/2vycg12

78. Jonathan Harvey: String Quartet No 3 (1995).

Textures are highly fragmented but there is underlying structure. Influence of electronics. (The Fourth Quartet of 2003 was to explicitly add live electronics). https://bit.ly/2USWhEX

79. Adrian Jack: String Quartet No 3 (1996).

No less than the Arditti Quartet rescued Adrian Jack from total recorded music oblivion, with recordings of four of his six quartets, the third is his most traditional. https://bit.ly/2IVrNjW

80. Leonard Salzedo: String Quartet No 10, op 140 (1997).

One movement, but defined sections: a characteristic perpetuum mobile presto, an andante with solo cello, a weird pizzicato scherzo, and a fugal allegro. https://bit.ly/2PGyG9F

81. Nicola LeFanu: String Quartet No 2 (1997).

Carrying on the string quartet tradition of (and dedicated to) her mother Elizabeth Maconchy. Musical equivalent to a sonnet. “Points of unison act like rhymes.” https://bit.ly/2VzAHK7

82. Sally Beamish: String Quartet No 2, Opus California (1999).

Reflection on Beethoven’s op 18 No 4. In the first, “Boardwalk”, tiny fragments come together into a sequence of sprung rhythms, approaching jazz. https://bit.ly/2H29N4n

83. Mervyn Burtch: String Quartet No 13 (2000).

Burtch wrote 17 quartets between 1985 and 2013, one of the most significant contributions to the genre to come out of Wales. https://bit.ly/2WhSFxR

84. Stephen Dodgson: String Quartet No 6 (2001).

Five continuous neo-Baroque style movements. Dodgson wrote nine numbered quartets between 1984 and 2006, and four much earlier unnumbered ones between 1948 and 1959. https://amzn.to/2IT9j3K

85. Peter Maxwell Davies: Naxos Quartet No 1 (2002).

The first time a record company sponsored a cycle of compositions? Ten Naxos quartets commissioned, composed, recorded (2002-2007). “Like ten chapters of a novel” (PMD). https://bit.ly/1Ve4AIZ

86. James Clarke: String Quartet No 1 (2003).

More “new complexity”, written for the Arditti Quartet and first performed at the Huddersfield Festival. Clarke has written four quartets, the latest in 2017. https://bit.ly/2WoyZZj

87. Sadie Harrison: Geda’s Weavings (2004).

Three movements, draws together strands and threads on a Lithuanian theme. Harrison was born in Australia but moved to the UK in 1970 aged five years old. https://bit.ly/2DGbymG

88. Dave Flynn: String Quartet No 2, The Cranning (2004–2005).

Heavily influenced by the techniques of traditional Irish music. “Cranning” is ornamentation used by Uilleann Pipe players. https://bit.ly/2XZwf4F

89. Michael Finnissy: String Quartet No 2 (2006-7).

Starting point is Haydn’s op 64 No 5 which sometimes emerges in blurred and distorted form. With no score, the parts are intended to drift slightly apart. https://bit.ly/2vvaMo9

90. Matthew Taylor: String Quartet No 5, op 35 (2007).

“Adopts a pacifying process as a volatile Allegro unfolds into a spacious fugue before easing into a delicate lullaby”. Taylor has written eight quartets to date. https://bit.ly/2DJ3a5Z

91. Edward Cowie: String Quartet No 5, Birdsong Bagatelles (2008).

Made up of a cycle of short pieces inspired by the voices and flight characteristics of 24 common British birds and evocations of their habitat. https://bit.ly/2Y2EXiN

92. Mark-Anthony Turnage: Twisted Blues with Twisted Ballad (2008).

His second work for string quartet. Two of the three movements are reflections on music by Led Zeppelin, the middle movement a Funeral Blues. https://bit.ly/2UNLDze

93. Gordon Crosse: String Quartet No 2, Good to be Here (2010).

In contrast to new complexity, Crosse turned to simplicity after joining the Quakers in 2009. Now in his eighties, Crosse has written five quartets since 2010. https://bit.ly/2UWBtw5

94. Sally Beamish: String Quartet No 3, Reed Stanzas (2011)

Scottish traditional fiddle meets classical string quartet, reed beds at Aldeburgh and birds on the Isle of Harris. https://bit.ly/2DHqyRb

95. John McCabe: String Quartet No 7, Summer Eves (2012).

Haydn was the key reference for McCabe’s 4th Quartet (1982), and again for the 7th, his last. The sonata form first movement is one of his most “classical”. https://bit.ly/2LqsXGa

96. Christopher Fox: The Wedding at Cana (2013).

Inspired by Spanish old master painting The Marriage at Cana. Mash-up of modal dances on anachronistic pop tunes, mean-tone tunings. “Based on music played at weddings these days”. https://bit.ly/2IU2WgF

97. Helen Grime: String Quartet (2014).

Three organically developed movements, continuous and overlapping. Opens with a fast duo for violin and viola. After a substantial middle movement (the longest), concludes with a virtuosic moto perpetuo. https://bbc.in/2VdDZ6a

98. Colin Matthews: String Quartet No 5.

“Shot through with silence”, mostly subdued and introverted for its 11 minutes, but “glides briefly into full hearing range before disappearing behind a closed door”. https://bit.ly/2Vc5ZXY

99: Howard Skempton: Moving On (2016).

Skempton’s third piece for string quartet (after Catch, 2001 and Tendrilis, 2004). Diatonic themes, chromatic treatment, subtle changes in meter and tempo, ending in a waltz. https://bit.ly/303VMvp

100. Rebecca Saunders: Unbreathed (2017).

Limited pitches, complex textures. With the composer’s epigraph – “Inside, withheld, unbreathed”- this piece is an uncomfortable, intense, Beckett-like experience. https://bit.ly/2LGQIdB

101. Anthony Payne: String Quartet No 3 (2018).

Payne’s first quartet was composed in 1978. The second was commissioned by the Allegri Quartet in 2011. The Villiers Quartet is currently touring the third. Payne is steeped it the chamber music of Elgar, Bridge and Schoenberg. https://bit.ly/2V7j4Ng

I now own scores for all the Hans Gal 24 Preludes & Fugues. It wasn’t completely straightforward, but I’m slightly amazed that they are available at all. They are all late works. The 24 Preludes, all brief (none of them last over four minutes in performance) were written in 1960 when the composer was already 70 years old, and published five years later. He began composing them while in hospital “as a present to himself” according to Michael Freyhan’s notes to the Alada Racz premiere recording, issued in 2001. Gal himself called them “studies in piano sound, piano technique and concentrated miniature form”. They are also elegant and beautiful, ranging from the graceful late Brahms of No 24, the flowing 5/8 of No 19, and the surprising polytonality of No 21, which despite a right hand stave in C major (avoiding any accidentals) and left hand stave in F sharp major, still manages to sound (in Gal’s description for the whole set) “unconditionally tonal”. I don’t think there’s a dud among them, but one of my favourites is Prelude No 7, “just” a study in using the thumb to cover seconds, but the end sounding to me like Ravel at his most luminous

I now own scores for all the Hans Gal 24 Preludes & Fugues. It wasn’t completely straightforward, but I’m slightly amazed that they are available at all. They are all late works. The 24 Preludes, all brief (none of them last over four minutes in performance) were written in 1960 when the composer was already 70 years old, and published five years later. He began composing them while in hospital “as a present to himself” according to Michael Freyhan’s notes to the Alada Racz premiere recording, issued in 2001. Gal himself called them “studies in piano sound, piano technique and concentrated miniature form”. They are also elegant and beautiful, ranging from the graceful late Brahms of No 24, the flowing 5/8 of No 19, and the surprising polytonality of No 21, which despite a right hand stave in C major (avoiding any accidentals) and left hand stave in F sharp major, still manages to sound (in Gal’s description for the whole set) “unconditionally tonal”. I don’t think there’s a dud among them, but one of my favourites is Prelude No 7, “just” a study in using the thumb to cover seconds, but the end sounding to me like Ravel at his most luminous Bernard van Dieren is perhaps the archetypal neglected composer – hailed as a genius by a small group of followers during his lifetime, hardly a note of his has been heard in the concert hall since his death in 1936. But how neglected is he really? Below is a chronological list of (arguably) his major works. Those marked with a star – 12 out of 22 – have been recorded in one form or another. On top of that, there are recordings of

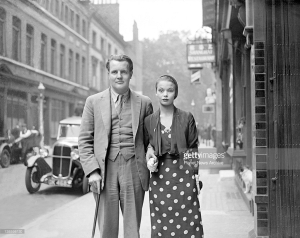

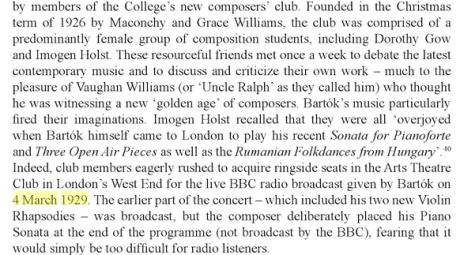

Bernard van Dieren is perhaps the archetypal neglected composer – hailed as a genius by a small group of followers during his lifetime, hardly a note of his has been heard in the concert hall since his death in 1936. But how neglected is he really? Below is a chronological list of (arguably) his major works. Those marked with a star – 12 out of 22 – have been recorded in one form or another. On top of that, there are recordings of  The extract below is from Lutyens, Maconchy, Williams and Twentieth-Century British Music: A Blest Trio of Sirens, by Rhiannon Mathias (2012). In the front cover photo above Elizabeth Maconchy is on the left, Grace Williams is in the center and Elisabeth Lutyens on the right.

The extract below is from Lutyens, Maconchy, Williams and Twentieth-Century British Music: A Blest Trio of Sirens, by Rhiannon Mathias (2012). In the front cover photo above Elizabeth Maconchy is on the left, Grace Williams is in the center and Elisabeth Lutyens on the right.

Due out on October 8th, John Seabrook’s new book The Song Machine is an expansion of a

Due out on October 8th, John Seabrook’s new book The Song Machine is an expansion of a